Revisiting: An Illustrated Life

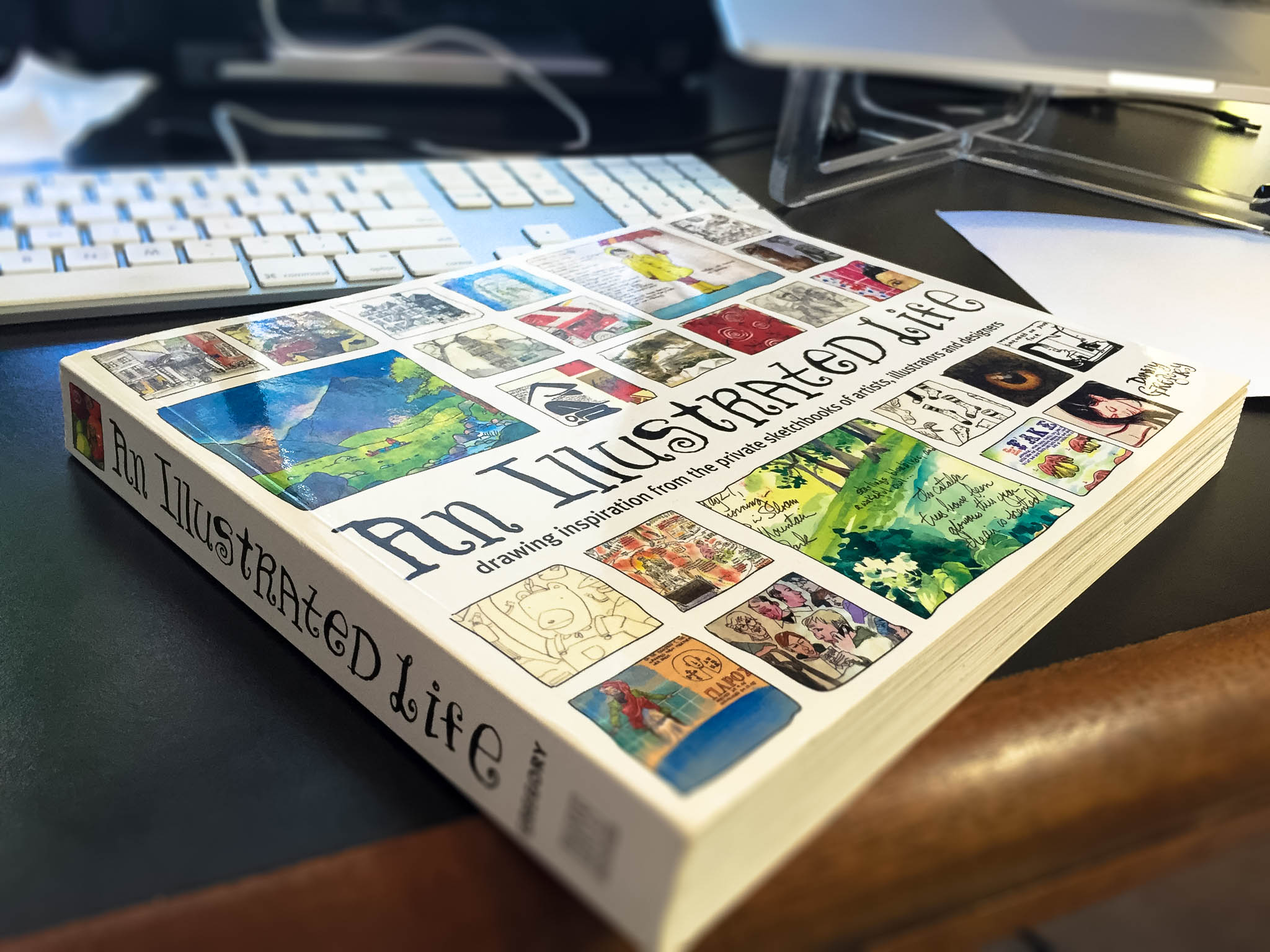

Back in the spring of 2008, during a trip to New York City, I visited with Danny Gregory at his house. Danny edited (and invited me to participate in) An Illustrated Life — a luscious, full-color-throughout, 272-page tome featuring a “sneak peak into the wildly creative imaginations of top illustrators, designers and artists from around the world through the pages of their personal visual journals,” and I was lucky enough to have my work showcased alongside such luminaries as Stefan Sagmeister, R. Crumb, Christoph Niemann, James Jean, Peter Arkle, Cathy Johnson, James Kochalka, Brody Neuenschwander, Chris Ware, etc. In addition, Danny interviewed each artist and shares their thoughts on living the artistic life through journaling.

I got off the subway and was invited in as Danny, his wife Patti, and his son Jack were in the middle of trying to make linoleum prints. Danny showed me his podcasting setup and pressed record, and we talked “about Art, Life, God and the rest of it”

Anyway, I went back to Danny’s site and noticed that the podcast itself was down; in its stead, I’ve coped-and-pasted excerpts from our initial written interview, below, which contains some of the same ideas. It’s very interesting to go back and hear the words I chose back then. If anyone can track down Danny’s podcasts, I’ll post it here as well.

Interview for An Illustrated Life, Spring, 2008

Danny Gregory: How did you first think of creating a graphic supplement to the Lectionary?

Paul Soupiset: The idea germinated a few years ago while I was planning weekly worship services for a fledgling faith community here in San Antonio. Part of my weekly preparations was to design and create a printed order of worship. One of the ways I would process the lectionary text was to create these liturgical sketches, usually inspired by ancient — Celtic or Byzantine — themes. Some of those resultant ideas, poems, or sketches would find their way into the worship service. “Wouldn’t it be cool to open a book full of this stuff?” became the question. I’m not sure who voiced it first, me or another person in the community.

About this time I also became re-acquainted with the liturgical illustrations of Steve Erspamer — a Marianist monastic whose amazing work has been mis-categorized by some as nothing more than liturgical clip art. His work focuses on the liturgical calendar, so I’m sure that was a part of the inspiration. The style of the book is growing organically but combines traditional and digital elements.

Danny Gregory: When you are drawing or designing, do you think of your creativity as worship?

Paul Soupiset: Definitely. I see every creative act as worship — participation in the Imago Dei — as long as I am being present to the creative action at hand, and being thankful to and aware of God during the process, worship happens. The amazing thing with [the way I see the arts] is that there’s sacredness in the conception, then sacredness in the creative action or execution or performance, and then, quite apart from the artist, there’s this recurring sacredness dealing with the artifact itself. […]

When I am drawing, sketching, painting on my own time, for my own purposes, at my own speed, I am usually aware of this and use the time as a kind of prayer-rhythm. However, when I am drawing or designing or art directing and it’s not on my own time, like up at the studio, it’s usually not until the end product that I’m able to look back […]

Danny Gregory: As a designer you work in a digital environment, and do not necessarily ever have to meet people face to face. In this new type of digital business world, how are you a witness to your non-Christian clientele?

Paul Soupiset: In the hundred of clients I’ve had, there have been probably fewer than a dozen that I haven’t met face-to-face. So, although the final execution of much of my work is digital, the vast majority of my creative work-life involves the messiness of real people and face-to-face meetings and spilled coffee and coughs and sneezes and co-workers dropping in to vent and all that stuff. I’m not very cloistered at all during my 40-hour-a-week career as a graphic designer, and with four kids, my wife and I are not very cloistered during the rest of the hours of the week, either. I guess for those reasons I tend to romanticize the monastic life. You can also see why I feel the need to steal away almost every lunch, and try to sketch.

But back to your question: I feel that as a Christ-follower, I’m called to simply […] let my work be a witness, and then to back off and let that witness be what it is, tattered and torn and bruised and faltering as it is. Then in strange ways the kingdom of God in-breaks and you get to participate — in that sense the witness is usually conversation- and story-centric, and less often design-centric. Those kingdom stories usually center around co-workers and associates and summer interns and job applicants and vendors and the folks that make my coffee next door probably more than it does my clientele, or at least in more visible ways.

Danny Gregory: Anyone who visits your blog will see very quickly that you have your hand in many different creative arts. You are creating the graphic art lectionary, you have art for sale, you have moleskine drawings, you are involved in church music—do these different arts interact with each other in your mind? Do your drawings become paintings, chords become drawings, artwork become a musical expression?

Paul Soupiset: I wish I were that integrated! Sure, sometimes a pencil sketch has grown into a painting, or a haiku gives way to a poem — which then gives way to a song lyric, but I think most of the time it’s more of a case of cross-pollination of motifs. There are little themes that come out again and again just because of who I am and the places I’ve traveled or the books that I’ve read — my music and my sketches both contain vague literary references, they elevate wordplay, they frequently invoke angels and saints, coffee and water, wine and bread, performative symbols, as the late Robert E. Webber would’ve said, that trade in deeper meanings.

One exception is a poem I wrote ten or twelve years ago, Appreciating Your Chicago: the words have resurfaced as a song, as a painting, and as a resultant photograph.

Danny Gregory: Makoto Fujimura, the increasingly popular abstract artist, once said of art critics that, “They don’t know what shelf to categorize my works on. They do see the obvious religious dimension, but, even if they like it, it is out of their semantics as contemporary critics.” Do you find that in the creative arts critics and artists no longer can engage with religious expression or metaphor?

Paul Soupiset: I think that critics, like many of us, are tired of Christians, sitting distanced and disengaged from culture, then creating art-as-propaganda and complaining when it doesn’t find currency in the art discourse. So, much of their critique is valid. Very few artists have learned how to authentically integrate their faith-expression and the zeitgeist. Mr. Fujimura has obviously found a vocabulary for both, as have others — Mary McCleary and their cadre at CIVA and IAM comes to mind. Once the artist’s authentic vocabulary is in use, art ceases to become pedantic or prescriptive.

Danny Gregory: When creating your liturgical sketches, do you have a palette for each season of the Church calendar? Do you emphasize the colors of each season in the corresponding sketches? Or is your work more abstract than that?

Paul Soupiset: I don’t prepare specific palettes for each season, but stay aware of liturgical colors and pay homage to them from time to time in my sketches. For Liturgical Sketching, I’ve been more intentional about this than usual, and find myself going back and tweaking works once they’ve been digitized to have a color flow from page to page. Unrelated, I was able to create a liturgical color palette for a Presbyterian church in Austin, Texas, and I really enjoyed the process; they recently came back to me and asked me to add a new light blue for their Advent usage.

Danny Gregory: Graphic art has been much maligned as inferior to the novel or nonfiction works. Graphic novels, save for the works of Frank Miller or Art Spiegelman, are treated as second class citizens in the literary world. Have you though of any ways to rid the world of this dichotomy? Do you have to argue against it, or is the best way to let the art speak for itself?

Paul Soupiset: I think time will shift the emphasis. I am one who believes that as we move out of the Enlightenment project, we shed our reliance upon language and its certitudes. The last half-century we’ve been easing into a long post-discursive era wherein symbol will reign supreme over words. Those who would pounce at Spiegelman will eventually skitter off into the distance or die off.

Danny Gregory: What do you count as artistic influences?

Paul Soupiset: Urban decay, found objects, Faulkner, Byzantine iconographers, the journals of Dan Eldon, Von Glitschka, da Vinci’s journals, letterpress make-readies, long lunches in small off-the-beaten-path cafés, Sigur Ros videos, Shakespeare, Marlo Chase, Neil Finn, Steve Erspamer, Hatch Show Print, Robert Tatum, [my mom] Pat Soupiset’s sculpture, watercolor, painting, batik, and stained glass work; the writers of the Psalms, Fauré, Erik Spiekermann, Tobias Frere-Jones and Jonathan Hoefler.

Danny Gregory: In particular, in your liturgical sketches, do you seek out art such as Eastern Orthodox ikons or the artwork of the early church to find liturgical inspiration? Any other Christian influences?

Paul Soupiset: I typically go to the texts first, and then sketch. If I choose to quote from an earlier ikon, I may go research and emulate. I pretty willingly throw myself into the great stream of tradition we have in pre-modern Christian art — both Western and Eastern. I may be as inspired by a Celtic gravestone as I am by a bookbinder’s gold leaf tooling on the edges of an Anglican Daily Office. Both are little visual artifacts that add to a grand vocabulary.

But my influences and inspirations are myriad. I’m working on a sculptural series that may take me another year, it’s the Stations of the Cross, and my visual influences on that particular piece are only modern and secular in nature.

Danny Gregory: Once the Year B liturgical sketches are finally finished, what is the game plan from there?

Paul Soupiset: Pray that a publisher is willing to take them to press: it’s an uphill battle, though: very few out there would be willing to publish a full-color-throughout book from an unknown artists. Luckily I’ve had quite a few pastors who have let me know they’d gladly stock their pews with multiple copies if it ever sees the light of day.

Then it would be time to start Year C, of course 🙂

NOTE: Here is where the formal written interview stopped; I also found some plenary questions he asked all of the book’s participating artists in July of 2007:

Danny Gregory: Where did you grow up and where do you live now?

Paul Soupiset: In 1969 my twin brother and I were born in San Antonio, Texas to an artist mom and a homebuilder dad. I made the choice after college to move back and pursue a graphic design career here in San Antonio.

Danny Gregory: What do you do for a living? Where?

Paul Soupiset: By day I’m creative director and a practicing graphic designer at Toolbox Studios, a company I helped to launch a dozen years ago. Our studios overlook the Riverwalk in downtown San Antonio.

Danny Gregory: Did you have any formal art training?

Paul Soupiset: I was a studio art minor, and my concentration for my journalism major was in advertising design, but I think my real training was being a curious kid sitting on a barstool and watching my mother sculpt clay, paint watercolors, prepare vats of dye for her batiks, draw, and occasionally cut stained glass — and then hanging out at my dad’s office, studying blueprints and his all-caps, architect’s hand-lettering. Much of what I’ve done since can be traced to the wide-eyed wonder of childhood.

Danny Gregory: Do your sketchbooks have a purpose?

Paul Soupiset: Some of my sketchbooks are travelogues — they serve as a visual book of days; some of my other sketchbooks are the places where I collect thumbnails for my client work. Lots of time they’re just how I blow off steam: at lunchtime, I’ll duck into a little taqueria downtown and engage in wordplay, cartooning, or sketching my environment.

Danny Gregory: Are your sketchbooks a record of your life? Or are they a laboratory to try out ideas that will ultimately be fully realized in another form? Or are they a playground? An obligation? A secret lair? Are your sketchbooks your true art form? Or just a springboard? Does the term ‘illustrated journal’ seem appropriate to what you do?

Paul Soupiset: Lately I’ve been ignoring my larger scale paintings and making my Moleskine sketches my primary medium. I retreated to sketchbooks as my primary medium when I got frustrated and impatient with painting. The end product of a painting usually comes so much later than the initial inspiration that meaning became lost for me; I was thinking more about my audience and less about the inspiration and subject matter. The journals retain a sense and a reality of intimacy and immediacy, even when being shared.

Danny Gregory: Is your book a constant companion? When do you decide to take it with you? Or do you mainly work in it at home or in your studio?

Paul Soupiset: There’s usually a Moleskine in my backpack, but I’m not disciplined enough to take it everywhere I go unless I’m in the middle of an assignment. I work in phases, being heavily inspired for maybe a month at a time, then letting the books sit, sometimes for weeks on end.

Danny Gregory: Do you have a sketchbooking ritual? A time and place to draw in your book? Or is it a spur of the moment thing?

Paul Soupiset: I’ve recently noticed that my energy and inspiration to create frequently arrive with a change in the weather: the onset of spring, or the first windy day in autumn, or an unexpected thunderstorm, something like that.

Danny Gregory: How important is the fact that your sketchbook is a book? That it has covers, that you can turn pages, that you can put it on a shelf, etc? How is drawing in a book different to you than just drawing on a loose piece of paper or on a canvas, etc?

Paul Soupiset: Codex books are objects of desire. They impart a feeling of permanency and collect-ability.

Danny Gregory: What is the relationship between your sketchbook and the work you do for professional purposes? Is there a difference in the process, the relationship?

Paul Soupiset: I’m much more disciplined at work because there we adhere to a formal process — each team member, each project, follows a discovery process prior to turning on the creative engines — at work, the goal is to efficiently arrive at the best solution. When I’m sketching, however, process is kept to a minimum; otherwise it would be drudgery. Margins and grids and baselines become deconstructed. Our designers’ sketchbooks are also teaching tools around the office, especially when talking to student groups and interns about the importance of thumbnailing and handwork and not rushing off to work out ideas on the computer. We still present tight pencil thumbnails for our initial client proofs instead of computer roughs whenever feasible.

Danny Gregory: What role does your journal play in your spiritual life?

Paul Soupiset: Many of the sketches shown here are part of a Moleskine watercolor journal series I began in February 2007: I embarked on a daily discipline of creating simple watercolored sketches during Lent (a 40-day period of self-examination observed between Ash Wednesday and Easter in more orthodox Christian traditions), primarily a means for me to slow down and be still every day during the 40 days period. It’s an imposed discipline wherein i must sit still long enough to breathe, consider the blank page before me, and pour myself onto the page with intentionality. Yes, to express myself, and then to share with God, with the viewer as well. Adding the color made each session last a little longer, teaching me much-needed patience — the watercolor must dry before i scan it, for example. One might think that lenten art ought to be rendered in greys, perhaps using rustic vine charcoal or comprising still life tableaux. Instead I chose whimsy, humor, vivid color… My journal also lets me pray and participate in the act of creation. There’s this term in the Hebrew scriptures, the Imago Dei — this idea of being formed in the image of a Creator God who in turn delights in our creativity.

Danny Gregory: What rules do you have about your book? Some people must fill every part of a page, other must make captions or headlines, some use particular media in particular books or have different books for different subjects? What are your rules?

Paul Soupiset: Some of my books are pen-and-watercolor only – the Moleskine brand watercolor journals. Now, I’ve got large “office Moleskines” for client thumbnails, a small “GTD Moleskine” that organizes my life, and my sketch journals as well.

Danny Gregory: How do you feel about blank pages? About the very first page in a brand new book? Is it intimidating? Challenging? Nothing important?

Paul Soupiset: I always leave the first page in a journal blank, and then the second page usually has some sort of introductory micro-cartoon or fragment of poetry. Sort of an invocation.

Danny Gregory: Do you feel your pages should be designed, that your drawings should bear some relationship to the overall page?

Paul Soupiset: Yes. And, frequently, no.

Danny Gregory: Do you doodle? In your book?

Paul Soupiset: I’m a doodler. Marginalia is a huge part of my art; I can’t help it. The doodles act like a greek chorus, commenting on the main scene.

Danny Gregory: Do you use your book to give yourself assignments, like drawing specific things or in specific ways?

Paul Soupiset: Yes, I can’t help it.

Danny Gregory: How has your sketchbooking changed over time? When did you start doing it?

Paul Soupiset: This loose chronicling style feels very natural for me; over the last two decades I’ve kept ongoing journals full of cross-hatched travelogues and layered collage elements that inspire/fuel my other art (paintings, songwriting, etc.). I was very inspired at one point by the Journals of Dan Eldon… but when I was handed my first Moleskine journal as a gift around 1999 or so, I was hooked. My journals have become less discursive and more visual as I get older. I like that. They actually say more, now, in a way.

Danny Gregory: How do people around you (family, friends, strangers) feel about your drawing in your book? Do you withdraw, disappear into it? Is it a performance?

Paul Soupiset: I have to distance myself from family and friends when I draw, which is why I go off at lunchtime to sketch when the weather’s good; for some reason I have no problem whatsoever drawing in front of strangers.

Danny Gregory: When you travel, how does your relationship with your book change? Do you ever go somewhere in order just to draw it? How does drawing a place help impact your experience of it?

Paul Soupiset: When I’m on a roadtrip, every rusty gas station, every side road telephone pole, every water tower is a potential sketch; and every pitstop an opportunity to draw. A small digital camera helps if you don’t mind occasionally drawing from a photo. Drawing from memory is so much more rewarding, though. I love traveling alone: I’ll look a small town, pull off the highway, find a nondescript diner and sit and eat and sketch. For the last four or five years I’ve been photographing old highway overpasses with the intention of turning all those shots into drawings sometime soon.

Danny Gregory: Are you particular about the sort of sketchbook you draw in or will you just use anything handy? Do you have a very specific type of book you like best? Where do you get them?

Paul Soupiset: I use and recommend Moleskine brand watercolor journals if you plan to introduce watercolor to your sketches. The paper is archival and the leafs are perforated so you can send sketches out at postcards; when my wife and I travel, we like to sketch the B&B or guest house we stayed at, and then leave the sketch as a thank-you.

Danny Gregory: What media do you use in your book? What specific (brands, sizes) pens, paints, etc?

Paul Soupiset:

• Staedtler pigment liners (4-pack: .01, .03, .05, .07 mm), black

• Moleskine water color notebook, large

• Windsor & Newton artist’s watercolor compact set (11 cm × 13.5 cm)

• All of this is small enough to fit in a large jacket pocket or the smallest pocket in my $5 Gap backpack.

• I try and take these supplies with me on every vacation, every road trip, and lately, I keep them with me everywhere i travel.

Danny Gregory: Where do you keep your books? Are they kept together? Do you consider them to be important objects, precious? Or are they purely functional?

Paul Soupiset: Precious, to be sure, kept on my bookshelf.

Danny Gregory: How do you feel when you look back through the books you’ve filled?

Paul Soupiset: Sometimes I’m surprised by what I find when I look back through old journals. That’s the best part.

Danny Gregory: Do you have any advice to give people about drawing and keeping a sketchbook?

Paul Soupiset: Take some time to create a drawing kit ahead of time, and leave a journal in your backpack, one in your suitcase, one in your glovebox, since you don’t know when inspiration will hit.

[recent_posts type=”post, portfolio” category=”” count=”1, 2, 3, 4″ offset=”1, 2, 3…” orientation=”horizontal, vertical” no_image=”true” fade=”true”]

Related Posts

Advent 2015 Sketchbook

November 30, 2015

Terminal Minotaur

October 15, 2015

Revisiting: Halo I & II

September 28, 2015

Hand Lettering: All Is Not Lost Noisetrade Sampler

September 26, 2015

Drawing Close: Mini-Documentary by Kyle Isenhower

September 22, 2015

Recent Dimensional Paintings

September 20, 2015